Ben Lerner

in conversation with Zoë Hitzig

Ben Lerner is a prolific poet and novelist. Beginning with The Lichtenburg Figures (2004), he published three award-winning books of poems. Then, in the decade that followed, he published three acclaimed novels—most recently The Topeka School (2019), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize—and a book-length essay called The Hatred of Poetry (2016). Upon the announcement of his fourth collection of poetry The Lights (2023), I and other steadfast fans of his poetry felt a kind of relief that brightened into delight. As one reviewer declared: “Ben Lerner the poet is back!” In our conversation, Lerner corrected the narrative: The Lights does not really mark a return to poetry. Instead, this new collection is the result of an excavation of the decade-worth of poems that he never stopped writing—the poems that both brooded the novels and hatched in them. We spoke about aliens, folk music, parenthood, the drama of recontextualization and the dystopian impulses behind our dreams of universality. Lerner also proposed a new CAPTCHA test. Our conversation took place at a wine bar in Brooklyn in October 2023.

ZH

Whenever a poet writes a novel, I can’t help but worry that the novel will be a catalogue of observations that didn’t deserve to land in a poem. What is possible in a novel that is not possible in poetry?

BL

Maybe I found myself writing novels because I embraced their secondary relation to poetry? I’ve always been interested in what happens when poetry is excerpted or embedded in prose—the narrator of Leaving the Atocha Station talks about this, the glimmer of possibility when line breaks are replaced with slashes. Or the little interval of whitespace between prose and a poem cited with its lines intact: that transition or threshold or leap—it reminds me of how Brecht was fascinated with that embarrassing yet beautiful moment in a musical when a grown person on stage bursts into song. It’s a transition that’s unaccountable, or even somehow unjustifiable. Those changes of phase are full of possibility (and always risk embarrassment). Like when the lights come on at the end of the play, or when the theater dims at the beginning of the play; a transition between levels, between worlds. The absorptiveness or elasticity of the novel means it can be full of such charged transitions. So hopefully it’s not a catalogue of lines that didn’t make the cut but there are in fact possibilities specific to the novel’s distance or falling away from poetry. Sometimes secondariness (is that a word? It is, right?) enables powerful aesthetic experiences. When I read really good poetry in translation part of me is thinking: “This is an incredible poem—and it must only be a pale shadow of what it’s like to read it in the original language.” This faith that I’m having an intense experience of what’s only a pale shadow deepens the intensity. But anyway, the novel can be a powerful frame for poetic experience and sometimes secondariness can smuggle in its own specific intensities.

ZH

Part of what you’re saying is that the novel gives readers a way to encounter poems in a particular context, rather than in a vacuum or a void.

BL

Yes, and it lets you dramatize questions of poetic value, or transvalue poems. Like the heart of my last novel—or maybe one of its hearts; like a worm or octopus, a novel can have more than one heart—is the little ritual around the nonsense poem, “The Purple Cow,” that Adam and his mother have. It’s a poem she learned in childhood and she recites it to Adam and he pretends not to be able to memorize it. And for a variety of reasons that matter in the book this little ritual of passing language down—but passing it down with a difference—is central to the book. I just mean that the novel tests what value can be put into “The Purple Cow” and one of the goals of the novel is to invest this “light verse” with depth. I think all my novels involve experiments in recontextualization like that—not only with poems but centrally with poems.

Of course, I’m not sure I’ll write another novel.

ZH

Did you expect to write this new book of poems, The Lights? Was there a point when you thought that you might not write another book of poems?

BL

There was a point where I thought (although it wasn’t a thought I defended, maybe it was more a kind of compositional despair) that I might just go on writing poems (I’ve never not been writing poems), but not write a book. Then eventually, I thought, if someone was interested in all the poems, they could collect them. But I kept failing to have a specific vision for a fourth book of poems with its own specific architecture.

ZH

So The Lights is not the novelist Ben Lerner’s “return to poetry”?

BL

No, I never stopped writing poems, I just stopped having a sense of what my next book of poems would be. In the last decade or so I’ve done a lot of collaborations with artists—that’s where a lot of my poetry was going. And it was hard for me to see if the poems I was writing in conversation with those artists were specific to that occasion, or should also be separated from the images.

ZH

How did these collaborations come about? I’m particularly interested in the collaboration with Thomas Demand because his process seems to be in conversation somehow with your themes of recontextualization, artifice. In your collaborations, how does the poetry function in relation to the art—is it similar or different to the way poetry can figure into a novel?

BL

In the case of the book with Thomas the images fully preceded the sequence of poems. He asked me out of the blue if I wanted to respond to the images. You’re absolutely right that part of why I felt it possible to write in relation to his work is because of his own versions of recontextualization, his crossing of levels: how he reconstructs in three dimensions scenes he first encounters in photographs, for instance. (You could probably say a lot about secondariness and Thomas’ work). I think your question helps me see why many of the poems I wrote in conversation with artists that were site specific didn’t make it into The Lights—because the dramas of reframing that so obsess me were happening between the text and image, or within the book that combines them, and not within the texts as freestanding works. I was probably drawn to collaboration—among other reasons—because, as you suggest, it’s an experiment with some affinity to the kinds of experiments with poems or prose (or image and text—there are images in all of my novels) that drew me to the novel as a form. But the poems often weren’t portable.

ZH

Was there one collaboration that produced poems that could especially stand on their own?

BL

Yes, most of the prose poems from Gold Custody, the recent book with Barbara Bloom, are in The Lights. But it’s not just that they could “stand on their own” it’s that they could stand in relation to the verse, and that handing off motifs from prose to poetry in The Lights became another version of recontextualization that felt alive to me.

ZH

But the fourth book of poems was a problem for you.

BL

I somehow convinced myself I was doing something noble by waiting and waiting! As time passed, the question of the poetry book started to become puritanical—as if the next book of poetry would have to somehow make up for this horrible betrayal of having written these novels. Or that I had to wait until I had a book about which I was absolutely sure, no ambivalence about the work! Which clearly will never happen. And then, because I waited, I had this new kind of problem: I had way too many poems for a book. I was waiting to build the book up, to write the new thing, but also had to excavate the book from the already written, to figure out what to discard. These are unoriginal problems, I’m just trying to describe the impasse. And I kept thinking: the next poem will show me the true form of the book.

ZH

Did that happen?

BL

No. But a couple things did happen. One is that I went to Providence to visit Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop—it was actually the last time I saw Keith—and Rosmarie really challenged me about the poetry book. This is not typical Waldrop behavior. They are very gentle. Rosemarie doesn’t, in my experience, have a habit of telling people what to do. But she was just like: Where’s the book? And I was like, well, I am publishing all these collaborations. And she said that’s bullshit. Of course she didn’t say it like that. But she basically said: those books are expensive, no one sees them. You have the poems, figure it out. Anybody who knows Rosmarie knows that these weren’t her words, but I’m describing the feeling...that she was saying I had lost a kind of nerve. I took that seriously and got to work and stopped fetishizing deferral. Then I began to just ruthlessly cut and a framework emerged. I began to excavate the book from all this other stuff I’d written.

ZH

Presumably that’s a very different process from your earlier books of poetry? There were short intervals between your earlier books—your first two books of poetry, The Lichtenberg Figures and Angle of Yaw, were just two years apart, then your third book Mean Free Path arrived four years after that. Now, thirteen years later, we get The Lights. Is the difference that your earlier books were “projects” from the outset, or that they were collections of poems written in more compressed periods of your life?

BL

With the earlier poetry books, I discovered a form that I would then try to exhaust. There were certain architectural principles, which I would follow until there wasn’t anything else to add. When I was ejected from the form, I knew I was done.

And yes, as you say, the time is different. For The Lights, the amount of time it took to write the book had to become thematic—it had to become an aspect of the book. I was initially resistant to that theme. And I was also resistant to how much it wanted to become a book about having kids. But eventually I embraced the way the book is a braid of different times. And hopefully makes it own time.

ZH

What else made this excavation hard?

BL

The dialectic of inclusion and exclusion was hard to figure out. Some of the poems I cut were at least as good, on their own terms, as some of the poems I kept. I just hadn’t had to deal with that before in the same way because the formal rules of the previous books offered a much clearer principle of exclusion. By the way, do you know about how [John] Ashbery graded his poems with letter grades? Emily Skillings taught me this. But then, when he made a book, he didn’t want to have all A poems. A book of A poems was a boring book, he thought! I’m not quite like that, it’s not like I was trying to include a bunch of C- poems, but I did have a kind of crisis around a few poems. There were a few poems that I felt were realized poems but in hard to express ways were a net loss for the form as a whole. I realize what I’m describing is totally mundane for an artist—what do you put in the book or show, what do you withhold—but I’m saying that the formal variety and the temporal span of these poems made it much harder for me to see clearly what work had a place here. And I did include for instance a “slight” poem I felt added to the sense of the whole more than another much more substantial piece that I felt dragged the book a little. Even though the latter poem was, out of the context of the volume, probably better.

Oh, I was also confused about the question of which poems had been published before. Some of the poems appeared in the novels. The long poem from Marfa was excerpted in 10:04, and so when I was deciding whether to include it in The Lights, I struggled over the question of whether the poem had been published already, or not. It won’t surprise you at this point to hear that I ultimately embraced that recontextualization, that transfer of a poem from within the fictional world back into the space of the poetry book. Anyway, the novels incubate the poems and vice versa. One dreams up the other. And the way motifs or forms are handed off across the genres, that relay across books, is really important to me.

ZH

It sounds like that structural principle can be summarized by a line in one of the poems early in the book: “A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking”?

BL

Yes. And also: it’s an old formal dream for me to combine disjunction and directness such that they are hard to tell apart. To go against some of the New Sentence or Language poet pieties about disjunction, about non-sequitur. In my writing, maybe disjunction is not encountered as an avant-garde intervention, but rather as a way of registering the emotional pressures of an utterance...to encounter collage not as deconstructive but as a mimesis of a voice made up of many voices.

ZH

Is that collage of voices the “sound of our / collective alienation”? The voice of the mysterious lights that flicker throughout the book in endlessly varying forms? There are lights in the trees. Taillights on the Brooklyn Bridge. Headlights by Route 67 in Marfa. The blue light on a vape pen. A firefly. Stars. Who or what are “the lights”? Are they actual aliens? Muses? Ghosts?

BL

All of the above. The lights are definitely the imagination of alien contact. In the title poem of the book, they are presented most explicitly as extraterrestrial. But it’s also about the human possibility of a certain kind of mis-reading—how we experience atmospheric effects or light pollution or whatever as a sign of possibility or mystery. Unexplained phenomena represent a kind of otherness or alterity, but then come back to us as just a way of understanding our own alienated version of the self or collective. Bad forms of collectivity can become a figure for collective possibility, an old and inexhaustible idea.

That poem [“The Lights”] is one of the latest additions to the book. There was no book for me without that poem so I guess I was waiting, in a sense, for that to materialize.

ZH

When building a book, poets assign themselves these ridiculous exercises, like “Now I need to write the title poem.” Or “Now I need to write the poem that connects poem A to poem B but in the same form as poem C.” Sometimes you can do it but sometimes you can’t. Sometimes you can’t do it because you shouldn’t do it. Sometimes you can’t do it because you haven’t tried hard enough to do it. How do you tell the difference?

BL

It's all ridiculous. I don’t know! It really bothered me—some people would say oh, you’re putting together all these poems that you’ve written across a large amount of time, so it’s like a “selected.” And I was like, it’s definitely not that. But then I had to figure out what it meant to negate that idea of the “selected,” how to make sure the book realized a concept (but without becoming “conceptual”!), how the book could be a specific form that made its own time.

ZH

I like The Lights as a title because it feels grand but also kind of… forgettable?

BL

Yes, totally. Sweeping and forgettable—risking cliché, but like a cliché, demotic, accessible. But also hopefully a title that undergoes change in the book. That’s one way I think of titles—similar to what we were talking about regarding “The Purple Cow” or other kinds of recontextualization or transvaluation or whatever. How does the title change once you’ve read the book.

ZH

And it’s funny in contrast with the earlier books of poetry that have hyper-specific, scientific titles that you dilate and use as recurring ideas.

BL

Right. And the novels have very specific titles too—they weren’t named for scientific terms but their titles are all important organizing metaphors in different ways. So “the lights” is a real departure as a title. Also, I wanted a title that didn’t invite any googling.

ZH

Was that because you didn’t like how your past titles invited googling? Did you come to feel that your past titles were too specific or pretentious or something?

BL

It wasn’t a repudiation, but I did want a different kind of frankness or transparency. And again the way light is handed off between like “The Lights” or “The Dark Threw…” or “Contre-jour” or “No Art” etc. is just the circuitry of the book. Also, my first daughter’s name is light—her name is Lucía.

ZH

Your children appear most explicitly in the poem called “The Readers.” You imagine them reading your work and write, “I am afraid they will understand it or won’t, will see / something they should / not remember when I’m gone.” How has the experience of fatherhood changed your relationship to the page?

BL

Well, my kids often ask me about my “work.” Which is interesting because, for kids, there’s a very shaky line between leisure and labor—often their play is a kind of simulated labor. Plus, there’s the strange thing I bring up in The Hatred of Poetry about how all children are told that they are poets. And all of this is to say, when my kids ask me about what it means to be a poet, this ancient question about the social value of poetry is activated for me in a newly intense way. And this self-consciousness can kind of hover over the page. But also, what this poem takes on is this tension—unexpected for me in its intensity—between feeling like I’m always in a sense writing to or for them (those are distinct prepositions, distinct dedicatory propositions, I think) and feeling like I need to protect them from my writing (because it reveals too much, information I should “hold” from them). But then at the same time feel I need to protect my writing from them, to keep art from becoming a space where I’m censoring myself or trying to parent, because that would make boring art. And these questions have only become really alive for me during the time of the last couple of books—because now the girls can read.

ZH

Are there other readers that you think about as you write and edit your poems?

BL

Sometimes I’m imagining a very specific person, this man who lives in Porto, this woman who lives in Denver, whatever. But other times, part of the pleasure of the poem is that sense that it’s for everyone or no one, that it encodes messages that I didn’t originate, things I don’t know I’m encoding, that it’s a message in a bottle that might be received by an addressee I cannot picture. I feel like the prose is less mysteriously encoded in that sense, though of course one is always saying more than one means, and one can always be overheard in mysterious ways.

I also think about my poetry heroes, many of whom are dead. They weren’t my only heroes, but it’s significant that C.D. [Wright] and Ashbery are gone, because they were alive when many of these poems were written. But anyway, we go on writing for the dead. It’s better to write for the dead than to write for X, formerly known as Twitter. I was always eager to send my heroes my books while they were alive. The truth is—Ashbery was never all that interested in my poems. One of the great ironies for me is that he loved my novels but appeared indifferent about the poetry. When I sent him my novels, he’d write back with enthusiastic praise. When I sent him my poetry books, he was like “thanks for the book.”

ZH

Do you imagine any readers you don’t know?

BL

Yes, the unknown readers, whether there are five or five hundred of them. I don’t know how to write without the hazy imagination of that reader...without the hazy imagination that the poem might open a channel. I think you have to stay in touch with the mundanity and miracle of that possibility, that you emit these signals you might not fully understand and that they might be picked up, interpreted, in some sense passed on.

It’s sometimes hard for me (and I think most people I know) not to feel that that possibility of reception and transmission isn’t under direct threat by the hot takes, the shit posts, etc. It feels petty to mention it, but I just feel the pollution of it, the toxicity of it, and I am depressed and amazed by how many supposedly serious people—like people who have supposedly devoted their lives to literature—have succumbed to the debased rhythms and flattening and aggression of such “platforms.” I am mentioning it to acknowledge my own debasement—a purer artist wouldn’t care, and I feel how ruined my own attention is—and to just tell you honestly that when you ask me about “readers” I also think about those anti-readers, those trolls and attention frackers. And I see how much of what passes for writing—what calls itself an essay or a novel or a poem—can feel like a compilation of tweets, takes, whatever. OK but enough about that.

ZH

One of my favorite moments in the book is where the speaker describes taking someone else’s black wool coat—and finding a folded-up note that said “I know we’ve had a difficult year… What happened in Denver will never happen again.” That poem ends with the speaker saying, about the note in the pocket, “I felt, [it] was meant for me; folk music is for all of us.” What is folk music, really?

BL

Do you know Kafka’s story about Josephine—“Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk.” Josephine is celebrated because she sings the music of the mouse folk, she sings for her people. But then her talents are continually questioned by the mouse narrator, who keeps suggesting that what she’s doing is not really singing. It’s just a quiet piping, some kind of whistling. The title is translated variously but the tension is already in it, in the “or,” singer or folk. It’s one unforgettable formulation of this deep and fascinating poetic contradiction: On one hand, to be a good poet, you’re supposed to be singular—perhaps because of the intensity of your feeling or the intensity of the language through which you make that feeling audible. But on the other hand, there is a pressure to be representative. And how can you be representative if you’re exceptional! A lot of the tension built into lyric poetry has to do with this contradictory notion—having to be exceptional but also universal. This contradiction, I think, is what produces the ambivalence as well as the violent fury of the mouse narrator in the Kafka parable. I’m just saying that the question of “folk music” opens onto the question of the one and the many in fascinating ways.

ZH

The thing about the jacket…Did that actually happen to you? Did you take someone’s black wool coat?

BL

No…not quite.

ZH

It’s a familiar feeling to me—reading strangers’ heartbreaking comments on Neil Young videos on YouTube or finding a note on the back of an old needlepoint at the antique store.

BL

Yeah, it’s related perhaps to John Stuart Mill’s definition of lyric poetry as overheard speech. Suddenly, you’re interpolated into the overheard. I often feel addressed by something that wasn’t meant for me. I also often feel not addressed by something that was meant for me. There’s a utopian and dystopian aspect to both of those experiences.

ZH

I don’t see the darkness as readily. What’s dystopian about the ability to be moved across distance and time and culture by messages not intended for you?

BL

Well, the way you put it is beautiful and full of light and that’s basically what my book is focused on. But folk is a very scary word. Is that a sign of my Jewishness? To be excluded from the folk is a threat. What pops into my head here is the horrifying children’s game “musical chairs”—we’re all in a group, circling these chairs, listening to the music, but when it stops, one of us will be excluded! One of us will have nowhere to go, be marked as an outsider. I hated that game. I hated Duck, duck, goose. All I’m saying is that language, too, has its in group / out group rituals. But I’m also fascinated by the idea that one can feel intimately hailed by a kind of all-purpose language. Have you seen Good Will Hunting? Remember the scene where Robin Williams keeps saying to Matt Damon, “It’s not your fault”? The first few times Robin Williams says it, Matt Damon is like “Yeah, yeah I know.” But then by the fifth or sixth time Robin Williams says, “It’s not your fault,” Matt Damon bursts into tears. My friend Geoffrey and I were talking about how this is a kind of CAPTCHA test. If you look anyone in the eye and repeat five or more times, “It’s not your fault,” they’ll burst into tears. If they don’t, they’re probably not human. (It probably also works, as in Kafka’s “The Judgment,” if a father just screams at his son that he’s been selfish and should go drown himself—at least that probably works with most fathers and sons).

ZH

It’s like the test in Blade Runner, where they measure the physiological responses to emotionally charged questions to distinguish between the humans and the replicants?

BL

Yeah. Similarly, there is this great story Laurie Anderson tells about the first time she met her Buddhist teacher. I’m not going to get this right, but it’s basically like: the teacher asks Laurie: Why are you here? And Laurie is like: I’m having trouble finishing my new album or something. And the teacher says: “No, you are here because you’re in pain.” And Laurie is like: No, I’m feeling pretty good, actually, I was just hoping to get some techniques to improve my concentration or whatever. And the teacher: “No, you are here because you’re in pain.” And now Laurie has been working with this person for decades. Imagine if someone came over here, and asked you “Why are you here?” You’d say “Well, I’m here talking to this silly author for a magazine.” What if the interlocutor said, “No, you are here because you are in pain.” And what if the interlocutor kept repeating it, insisting on it? Wouldn’t you eventually feel addressed by that—you are here because you are in pain. You are here because you are in pain. There is something scary and beautiful to me that the repetition of these utterances could melt us. Our malleability before some of these all-purpose forms of address. That’s part of what’s happening with the message in the bottle of the wool coat!

ZH

I see. In The Hatred of Poetry you talk at length about Whitman’s vision of poetry as a technology capable of singing America into existence—and its inevitable frustrations or disappointments. Inside the expansiveness of folk music, and statements like “You are here because you are in pain,” lies a grand democratic possibility alongside a testimony to its likely collapse?

BL

Yeah, the changes in the aperture of the second person are part of the miracle and peril of literature … who gets to fit into the pronoun “you”? Sometimes I’m addressing “you” as an embodied individual, and sometimes I’m addressing “you” as a marker for an abstract possibility of an “other.” A song that makes the pronoun as capacious as possible isn’t really a song at all. It’s just a kind of quiet piping.

ZH

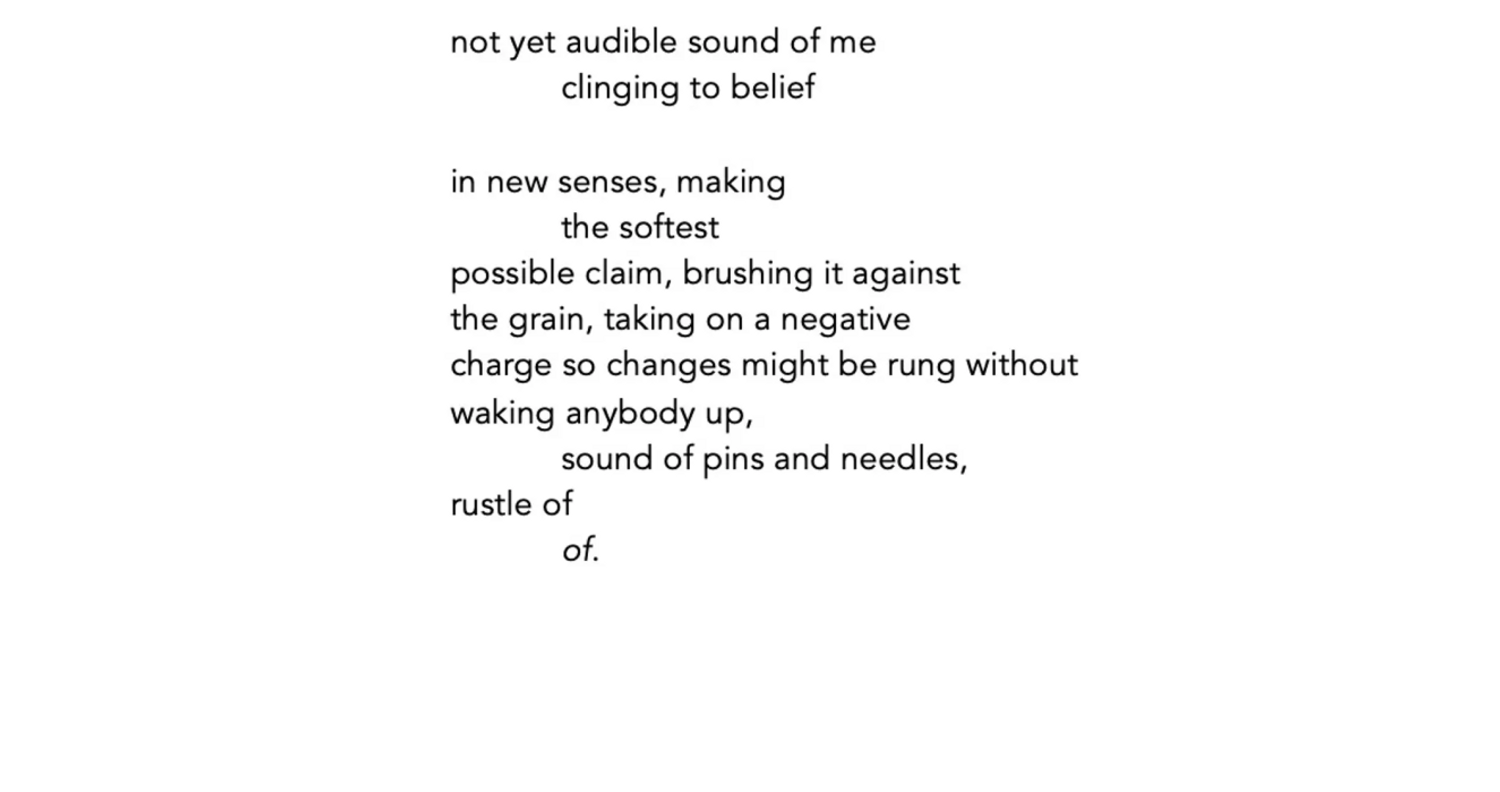

Or, to end on embedding some of your poetry in our prose, it’s the:

Next from this Volume

Doreen St. Félix

in conversation with Emmanuel Olunkwa

“I had always had in my head that criticism becomes criticism once it’s published.”